A sediment delta fills the west end of Lewis and Clark Lake near the confluence of the Niobrara and Missouri Rivers. The view, in 2016, is from Springfield, South Dakota, looking south toward Nebraska. The constant influx of fine sand and other sediment and the organic material that comes with it has created challenges for the regional water system in northeast Nebraska.

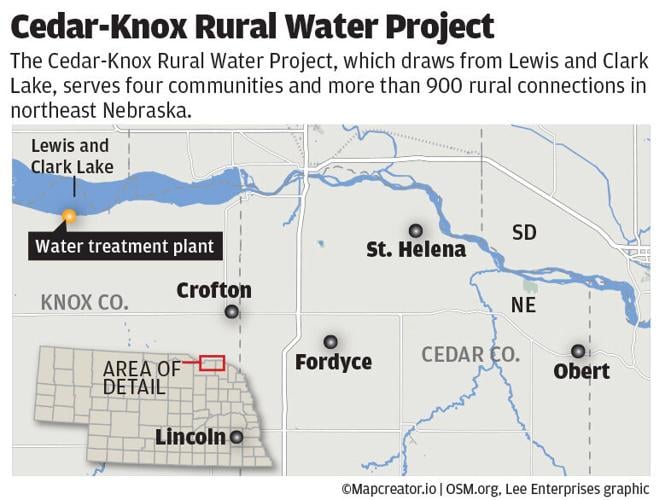

For more than four decades, the Cedar-Knox Rural Water Project has drawn water from Lewis and Clark Lake and pumped it into communities and homes across northeast Nebraska, some nearly 40 miles away.

But a constant influx of fine sand and other sediment and the organic material that comes with it has created challenges for the regional water system.

Rising levels of trihalomethanes, a byproduct of treating water with chlorine or other disinfectants to kill microorganisms or viruses, have become increasingly difficult to manage as more sediment moves into the lake each year, said project manager Scott Fiedler.

Better known as THMs, trihalomethanes have been linked to bladder and colon cancers, and are suspected of causing a range of other health issues affecting the liver, kidney and central nervous system.

In 1979, the Environmental Protection Agency set a maximum contaminant level for THMs in drinking water systems at 100 parts-per billion, but around two decades ago lowered that limit to 80 ppb, what Lewis and Clark NRD officials described as “a bigger hurdle to meet.”

People are also reading…

The Cedar-Knox Rural Water Project has until recently been able to keep its THMs level underneath the threshold deemed safe by the EPA, Fiedler said, but it's becoming increasingly difficult.

“At this point, we’re below the threshold,” he said. “It’s just a matter of time before it catches up to us.”

A growing problem

With the completion of the Gavins Point Dam in the mid-1950s, the lake once navigated by the Lewis and Clark expedition between 1804 and 1806 became Nebraska’s second-largest reservoir.

Stretching more than 25 miles end-to-end, and with a maximum depth of nearly 45 feet, Lewis and Clark Lake provides opportunities for camping, boating and other recreational activities, and is part of the Army Corps of Engineer’s broader strategy of managing the Missouri River.

In the late 1970s, the natural resources district headquartered in Hartington began exploring the possibility of creating a regional water system to serve northern Cedar and Knox counties, where groundwater resources were inconsistent.

At roughly the same time, a surface water treatment plant located near Devils Nest, a residential area overlooking the lake, came up for sale after the development fell into bankruptcy.

The Cedar-Knox Rural Water Project bought the plant in 1980, and a year later, began serving nearly 300 customers in the area, as well as the communities of Crofton and St. Helena.

Today, the water system also serves Fordyce and Oberst, both unincorporated communities, some 900 rural customers, as well as new housing developments overlooking the lake, according to Annette Sudbeck, general manager of the Lewis and Clark NRD.

But as the number of customers connected to the Cedar-Knox Rural Water Project continued to grow, officials kept watch of the encroachment of silt and sand on the western reaches of the lake.

The delta on the lake began shortly after the flow of water was changed on the Missouri River, according to Paul Boyd, a hydraulic engineer with the Army Corps of Engineers Omaha District office.

To date, the Missouri Sedimentation Action Coalition estimates 30% of the lake’s overall surface area has been lost due to sediment depositing into the lake behind the Gavins Point Dam, with 50% of the lake’s surface area expected to be lost by 2045.

Boyd said the delta can grow or change shape during significant weather events, which can flush additional sediment into the Lewis and Clark Lake.

Flooding on the Missouri River in 2011, for example, didn’t result in a “big additional inflow” of sediment, Boyd said, but redistributed the existing sediments already in the system, changing the shape of the delta in the process.

The 2019 flooding across much of northern and northeast Nebraska that was triggered by a bomb cyclone “likely brought in a fairly significant pulse of new sediment” from the Sandhills, Boyd added.

The changes are notable in satellite images taken over time. The Corps of Engineers is undertaking a survey to measure the recent changes to be published next year.

“If you hop on Google Earth and look at the imagery from the past 30 to 40 years, it’s pretty easy to see how the face of that delta is migrating from where it was originally on the South Dakota side, past Santee and getting ever closer to where Cedar-Knox has their intake in the lake,” Boyd said.

Each flood event can also bring more organic material into the body of water, or stir up the existing organic matter already present, raising the likelihood that the concentration of THMs measured by Cedar-Knox Rural Water Project will also increase.

Bruce Dvorak, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, said the presence of organics is a challenge for surface water systems, particularly when they are connected to areas that experience the full range of Nebraska’s seasonal changes.

“The amount of organics can vary month-to-month, or day-to-day even,” he said. “That’s one of the reasons in Nebraska that very few drinking water systems use direct surface water as a source.”

Fiedler said the Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy put the water system under an administrative order for the first time in 2017 after the concentrations rose above the threshold deemed safe.

The order was lifted soon after the water system took measures to control the concentrations of disinfectant, but Fiedler said the battle has continued ever since, resulting in another administrative order on Sept. 25, 2020, when the annual average concentration of THMs was reported at 81 ppb.

One quarterly test showed the disinfectant byproduct at 113 ppb, while another measured THMs at 101 ppb. Two other tests showed the concentrations at 45 ppb and 64 ppb, well below the levels deemed unsafe by the EPA.

In a letter to customers explaining the administrative order, the Department of Environment and Energy said in addition to routine flushing of the system, utility managers were working on a plan to install a second chlorine feed at the mid-point of the distribution system.

“This pilot project will allow lower chlorine levels at the treatment plant while maintaining the minimum residual disinfectant at the end of the system,” the department said.

Fiedler said the new treatment plant has helped keep THMs at bay since it was opened in 2021, but described it as a stopgap measure until a permanent solution could be identified and implemented.

Identifying a solution

In 2017, shortly after the state ordered Cedar-Knox Rural Water Project to make changes in order to bring down the level of THMs, officials with the Lewis and Clark NRD started working on a plan to move away from the surface water supply.

Working with an engineering firm, the natural resources district came up with a plan to replace the surface water drinking system, one of about five in use across the state, with a regional system supplied by groundwater, according to Sudbeck.

That would carry several advantages, according to Dvorak, who has advised water systems across the country for several decades.

Groundwater does not carry organic material the same way surface water does, reducing the amount of chlorine or other chemicals needed to treat it, he said, meaning it's safer and more economical for users.

The price tag for the project was $32 million at the time, but the cost of upgrading the system has likely risen — perhaps dramatically.

“After COVID and inflation,” Fiedler said, “we anticipate it could be double that.”

Sudbeck said the water system has sought help from the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund, a cash fund operated by the Department of Environment and Energy that offers forgivable loans to water systems seeking to upgrade their systems.

The project has been earmarked for a $25.2 million loan, a department spokeswoman said, with $12.6 million of that amount able to be forgiven if the project meets specific requirements outlined by the state.

Replacing the Cedar-Knox Rural Water Project’s connection to Lewis and Clark Lake with a new groundwater wellfield also got a $7 million boost from the Legislature in 2022, which appropriated American Rescue Plan Act funds for that purpose.

Neither the loan funds nor the federal dollars have been disbursed to the NRD, a department spokeswoman said.

State lawmakers also approved another $7 million in state tax dollars toward the project this year. The bill (LB768) from Sen. Barry DeKay of Niobrara, who represents Cedar and Knox counties, would have appropriated money to the state environmental department to award a grant to the water system.

Those funds fell victim to a line item veto by Gov. Jim Pillen, however.

In his veto message, Pillen noted the project “has already seen significant investment from the state” totaling more than $32 million — the amount indicated in the preliminary engineering report.

Sudbeck, in a phone interview in June, said the natural resources district was still examining its options to keep the cost of the project from falling upon the water system’s customers.

“We really want to make sure we can secure this system for the long term, but it will take additional support to get it across the finish line,” she said.

On July 31, the Cedar-Knox Rural Water Project got another boost when U.S. Sen. Deb Fischer, a member of the Senate’s Appropriations Committee, announced she had secured $10 million in the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies appropriations bill.

It was one of a dozen projects in Nebraska totaling $20 million included in the Appropriations Committee’s proposal, which advanced on a 28-0 vote.

“This funding bill will keep Nebraskans healthy and safe by investing in crucial water infrastructure projects across our state,” Fischer said in a statement.

Fiedler said the Cedar-Knox Rural Water Project is projecting breaking ground on the upgraded system next year, and anticipates construction will last three to four years before a groundwater system is brought online.

Once it does, he said the water system will not only provide a safer source of drinking water for existing customers, but foster economic growth in the area. Some communities have been limited in their growth because there was either no water available, or the water quality was poor, Fiedler added.

“This water project is just incredibly critical for this area,” he said.

Download the new Journal Star News Mobile App

Top Journal Star photos for August 2023

Kipton Fankhauser loses his shoe as he falls off of "War Dance" during Mutton Bustin' at the Lancaster County Super Fair on Tuesday, Aug. 8, 2023, in Lincoln.

Patrons enjoy the first weekend of the outdoor carnival during the Lancaster County Super Fair at the Lancaster Event Center on Saturday, Aug. 5, 2023, in Lincoln.

Syllas Daniels and Kaneka Taylor (right) hold on tight as they ride the Orbiter at the carnival during the Lancaster County Super Fair at Lancaster Event Center on Saturday, Aug. 5, 2023, in Lincoln.

A nun peruses the animals on display at Rabbit Row during the Lancaster County Super Fair at the Lancaster Event Center on Saturday, Aug. 5, 2023, in Lincoln.

Angelina Mojok waves to the camera as she rides the merry-go-round at the carnival during the at the Lancaster Event Center on Saturday, Aug. 5, 2023, in Lincoln.

Cally Sullivan, Hannah Munk, Noah Schmoll and his sister Jocelyn (from left) let their rabbits hop from the starting line as they compete in a rabbit race during the Lancaster County Super Fair at the Lancaster Event Center on Saturday, Aug. 5, 2023, in Lincoln.

Offensive lineman Yahia Marzouk and Brady Eickhoff (from left) spring out from under the chute while running a drill during a practice at Lincoln Northwest on Wednesday.

Nebraska middle blocker Andi Jackson blocks assistant coach Jaylen Reyes during practice Tuesday at Devaney Sports Center.

Lincoln Pius X's Hudson Schulz (left) tackles teammate Sebastian Morales during practice on Tuesday at Pius X High School.

A view of the Federal Legislative Summit on Tuesday at Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum in Ashland.

Nebraska's Bryce Benhart (left) and Brock Knutson practice on Tuesday, Aug. 8, 2023, at Hawks Championship Center.

Lincoln Southwest's Zak Stark makes a throw during a football practice on Monday, Aug. 7, 2023, at Lincoln Southwest.

An excavator tears bricks off Pershing Center on Monday as demolition work begins in earnest on the former civic auditorium. Bringing down the structure is expected to take two to three weeks.

Young dancers spin one another as they perform a traditional dance with Wilber Czech Dancers during the annual Wilber Czech Festival on Saturday. The celebration will continue Sunday with a parade, motorcycle show, eating contest and much more.

Teams shoot around in the common area as they prepare to compete against one another during the 3-on-3 Railyard Rims basketball tournament at The Railyard on Friday, Aug. 4, 2023, in Lincoln. In collaboration with the Downtown Lincoln Association, the YMCA of Lincoln hosted the seventh annual Railyard Rims August 4-5. This 3-on-3 tournament takes basketball to the streets of the Railyard.

Callum Anderson gets his first haircut from barber Dean Korensky as he sits with his mother, Courtney Anderson, on Thursday at 33 Street Hair Studio. Callum was the fifth generation of the Anderson family to get a haircut from Korensky.

Carter Worrell has a staring contest with a baby chick during the Lancaster County Super Fair at Lancaster Event Center on Aug. 3, 2023.

A Nowear BMX rider jumps from a high ramp while teammates watch during the Lancaster County Super Fair at Lancaster Event Center on Thursday.

Zack Mentzer peeks out from a trailer while he and his family unload their Hampshire cross breed pigs the day before the start of the Lancaster County Super Fair at the Lancaster Event Center on Aug. 2, 2023.

Fair kids who show animals will set up in the stalls so they have a place to rest, the day before the start of the Lancaster County Super Fair at the Lancaster Event Center on Aug. 2, 2023.

Jen Witherby (left) and Mary Weixelman, bought 3 Daughters, last month and just recently completed their first week as owners.

Cooper Jordan, 4, runs the spray of a soaker hose during Sprinkler Day at the Eiseley Branch Library on Monday.

Protester Kari Wagner holds up a sign as Nebraska State Board of Education member Kirk Penner walks by in the Capitol on Monday.

Mack Splichal, 2, shows off his cheer moves to Nebraska cheerleaders Sidney Doty, Carly Janssen and Audrey Eckert (from left) during Nebraska Football's annual fan day at Hawks Championship Center on Sunday, July 30, 2023.

Shoes lost by previous skydivers are hung above the exit to the runway at the Lincoln Sport Parachute Club on Saturday, July 29, 2023, in Weeping Water.

Carpet Land players watch from the dugout as their team bats in the first inning during the Class A American Legion championship on Saturday at Den Hartog Field.

Nebraska's Darian White (left) talks with teammate Callin Hake during a team practice Thursday at Hendricks Training Complex.

Ten-year-old Connor Horner plays in the sprinkler fountain at Centennial Mall across from the state Capitol on Monday, as temperatures reached the 90s and the heat index reached into triple digits. The Lincoln Parks and Recreation Department said it discourages people from playing in the Centennial Mall fountains because the water is not treated.