MUSIC INDUSTRY | TOURS

Today is the day. You called in sick to work. You've been looking forward to the chance to buy seats since the show was announced. The webpage loads on your laptop, and you're met with triple-digit prices for a ticket to see your favorite musician. In the seconds you spend hesitating, the entire concert is sold out. You quickly pull up a reseller site, and the prices are now four digits and climbing.

Taylor Swift fans saw a similar scene this year, as have masses of other aspiring concertgoers. How did we end up spending more than your average mortgage payment for a seat at a concert? The answer is ...complicated.

Why are concert tickets so expensive?

There are five major players influencing ticket prices: the artists, the promoters who put on the shows, the venues that host them, the ticketing companies that make the initial ticket sales and the resellers that sell seats no longer available from the box office.

People are also reading…

Each link in the chain is responsible for some portion of the cost of your concert-night experience, because each link is a business trying to make a profit.

Promoters are the connection between the act and the venue. They officially set the ticket prices, and they take on the loss if the concert doesn't generate enough ticket sales to cover what the artist has been guaranteed. They organize and publicize the shows, and those costs go into the price of the ticket.

Artists like Taylor Swift at the top of the industry can tell the promoter where to set ticket prices and also pick the venues. Smaller acts have those decisions made for them. According to Bob Lefsetz, a music-industry analyst and former label executive, the acts also have power over ticketing fees and resale policies if the primary ticket seller has its own resale platform.

Venues are paid by promoters to put on the shows, and the promoters get that money through ticket sales. Venues also might charge a facility fee, which adds to the slew of fees that show up at the end of your purchase. Some venues are owned by or have exclusive deals with promoters such as Live Nation Entertainment (which also owns Ticketmaster). Others are called "open buildings" that any promoter can book. Every building has a ticketing contract, however, which typically requires the ticketing company to pay in advance for the right to sell the seats.

Ticketing companies add the fees that can turn a $20 seat into a $35 seat. Here's the breakdown of the most common ones:

■ The service fee, also known as a convenience fee, is the amount tacked on for the privilege of buying a ticket online instead of at the box office. Ticketmaster says it sets the fees with the artists' input and typically shares the proceeds with them.

■ The processing fee is the charge added to each order (not each ticket) to cover miscellaneous expenses associated with online ticketing. The Ticketmaster website says that the processing fee "off sets the costs of ticket handling, shipping and support."

■ The delivery fee is the charge for getting you the tickets you order, and it varies based on which option you select. The DIY options, such as tickets you print yourself or store in your phone, tend to be free or low-cost; not so much for having physical tickets shipped to your home.

■ The facility charge is what helps the venue run the show. Artists decide if there is a fee and how much it is.

A 2018 report by the Government Accountability Office found that fees on initial ticket sales added 27% to the cost, on average. The lower the price of the ticket, however, the more burdensome the fees can seem.

Ticketmaster is this industry's Goliath, but there are other ticketing agencies handling smaller venues and acts. Their common goal is to get rid of software "bots" that quickly buy tickets in bulk, raising prices for hot shows by shifting tickets to the resale market.

Resellers and ticket brokers such as StubHub and SeatGeek create a secondary market for tickets that buyers can't — or never intended to — use themselves. Brokers compete with fans for seats in the initial sales, using teams of employees or software bots that snap up tickets faster than individuals can.

The GAO said that, according to the four resellers interviewed for its report, "professional brokers represent either the majority or overwhelming majority of ticket sales on their sites."

StubHub takes issue with the GAO's number; of the people who sold tickets through the site last year, it classifies less than 1% as brokers. Resale prices for tickets are set by the seller, although some resale sites will suggest prices for them. And this is where ticket prices can skyrocket, because the sites don't limit how much a seller can charge.

"This is a truly market-driven platform," StubHub spokesperson Jessica Finn said. "So this is really about what sellers think that the price, the value of the ticket is, and what buyers think the value of the ticket is, and they effectively agree on it with a purchase. … It's very much a dynamic marketplace, prices go up and down and we don't meddle with that."

Lefsetz said the secondary market sells tickets for the prices they do because that is what the tickets are worth. They wouldn't be on sale for those prices if people didn't buy them for that price. If they set the price too high, the tickets won't sell — for example, tickets for Adele's Las Vegas shows sold for an average price of $1,900, compared with the average listed price of $4,800, according to StubHub.

Resellers charge a similar array of fees to ticket buyers, but they add more on average to the cost of seats than the original ticket seller's fees do. University of Chicago professor Eric Budish, an economist who studies ticketing in the United States, found that resellers charged buyers and sellers fees amounting to 30% to 40% of the ticket resale value. "So if a Taylor Swift ticket resells for say $2,000, the secondary market site ... might be making 30% of that amount. Thirty percent of $2,000 is $600. Taylor Swift sold the ticket for say $300. So the secondary marketplace is making more than Taylor Swift is, and then the broker is making more than either of them."

Lefsetz says people want to sit in great seats without having to pay an exorbitant price for them; instead, they think they're entitled to sit there because of how much they love the artist. "Everyone thinks that it is only the ultra-rich who are buying four-figure concert tickets. No, there are people who are saving up. This is their favorite band."

What are the options for the future of ticketing?

The way Budish sees it, the industry has three economically logical options moving forward.

We could continue as we are with unrestricted reselling. Tickets go on sale at the price set by the promoter and, despite repeated efforts to confine sales to actual human fans, many get bought up by bots in seconds to be sold on the secondary market.

The next option is that the promoters set what is called a "market-clearing price," that is, a price high enough to prevent the tickets from being resold for more money, but low enough to attract a full house of fans. Ticketmaster has started trying to set market-clearing prices through a program it calls "platinum tickets," where it sells the most in-demand seats separately from the primary ticket offering. The company says that the goal of platinum tickets is to allow artists and promoters to set ticket prices that they think reflect their true market value. But the program can generate fierce backlash from fans, as Bruce Springsteen discovered last year when platinum ticket prices skyrocketed above $4,000.

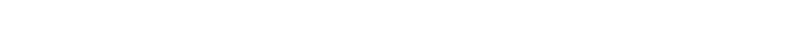

The final option is to restrict or end resale. Options for this route would be to make tickets nontransferable, allow resale only at face value and only on the primary seller's resale platform and use technology to attempt to identify real fans by looking for irregular behavior on their accounts. The Cure used all of these measures on its most recent tour. Lead singer Robert Smith advocated for his fans to the point that he convinced Ticketmaster to refund some of the excessively high fees on the tickets.