Laura Yeramysheva-Bley, her husband Jerrod Bley and their children (from left) Leopold, Cora and Embry, at the antique dining room table they found on Facebook Marketplace. The family furnished their Lincoln home with used items. They try to lessen their impact on the environment by reclaiming, reusing and recycling everything they can.

The dining room table, it’s not my style.

But it was my parents' style, and we ate every holiday meal there at the house they built after we all grew up and left home.

A bigger house. A house with the dining room my mom always wanted.

Cindy Lange-Kubick

What my dad wanted was to die in that house.

Now a dark-haired stranger was carting that table away from a place with call buttons and nurses — the retirement home my mom and dad had landed and where Dad would spend his last months.

His journey was a fill-in-the-blank primer on aging, as predictable as a sunrise. A stroke one year, a fractured neck the next, a life-changing fall on the driveway.

When I arrived at the east Lincoln cul-de-sac that spring morning in 2021, Dad rested on the concrete, a pillow under his head. His right foot jutted out at an angle, like a ballet dancer in third position. A sure sign of a broken hip, the doctor living next door told me.

People are also reading…

As we waited for confirmation in the ER, my dad turned to my mom: I’m sorry.

For years, Mom had nudged him to move into a senior living community. No yard work. No stairs. A built-in social life.

She was ready. He was stubborn.

Hell no, Dad would say. I don’t want to live with all those old people.

Dale Lange sits in the green armchair where he spent his mornings reading newspapers and pondering his day. The chair is part of a collection of furniture purchased secondhand by Jerrod Bley and Laura Yeramysheva-Bley in an attempt to save resources and do their part to slow climate change.

Now, the decision was no longer his. The house went on the market, and the first round of possessions disappeared. My sister and brother and I took what we wanted — the blonde bedroom set from their early years, Mom’s frosting knife, my granny’s potato pot, the birthday cards Dad saved in a shoebox — and they kept enough to furnish that first apartment.

My dad was an entrepreneur. He was a money-saver and a handshaker.

He was a storyteller. The first to laugh at his own jokes. The man who taught me to change my oil, bluff at pitch, go for broke but never swim out farther than I could swim back.

By the time his hip snapped, he was 87, and the slow slide to the grave had gained momentum. Nine months later, he and Mom were leaving the roomy independent living apartment at Legacy Estates for a smaller place in assisted living. Three months after that, he’d be gone.

That dark-haired stranger didn’t know any of those things.

Jerrod Bley simply answered a Facebook ad, handed over $100 and carted away that table where we had made so many memories. He grabbed the chairs, too, and the flat screen and the pale green armchair where Dad had lingered each morning for decades alongside my mom, in her matching chair.

Dale and Arly Lange, good neighbors and good people, reading the newspaper and plotting their day.

***

The dining room table found its next home on Plymouth Avenue.

The two-story house is nearly 100 years old, covered in weathered cedar shingles.

Jerrod Bley and Laura Yeramysheva-Bley live here with their fluffy dog and a trio of dark-haired children: Leopold, 4; Cora, 3; and baby Embry, a chubby and cheery 6-month-old.

A vintage armchair from Facebook Marketplace lives a second life in Laura Yeramysheva-Bley and her husband Jerrod Bley's home in Lincoln.

After years of far-flung moves, they’ve settled in Lincoln where Laura — born in Azerbaijan — grew up, surrounded by her extended Armenian family.

Jerrod is the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s sustainability manager, finding ways to reduce waste and save energy. Laura runs a small skincare business and is returning to school for her psychology degree this fall.

The first-time homeowners closed on their house in February 2022 with a goal: to furnish it entirely with secondhand belongings.

“We saw your family’s ad and said, ‘Let’s jump on it,’” Jerrod remembers. “It was the first thing we bought.”

The table is perfect in their dining room, Laura says. “It’s our most utilitarian piece and it’s beautiful.”

They eat all their meals there. They work there. The kiddos make art there. They entertain friends and family there.

It’s a sturdy symbol of their philosophy: to walk lightly on the Earth.

***

Dad never recovered from that broken hip.

Mom was his companion and caretaker, worrying over him, reading the newspaper aloud to him in the morning when his eyes failed, guiding his walker to the bathroom in the middle of the night.

I’d coax him down the hallway outside their apartment, with its hotel-patterned carpet and piped-in ’80s music, Dad shuffling to the beat of Queen and U2. He’d rest halfway, grumbling about the musical selections, and gratefully collapse in his recliner after our trek. “We made it!” he’d say.

Dale and Arly Lange with their three children Kim, Rick and Cindy in the 1960s.

He walked to please me, Mom told my sister later. To show me he hadn’t given up.

But by February of 2022, Dad was in hospice, and on his way down the long hallway in a wheelchair to assisted living.

The dining room table went off to Plymouth Avenue.

Dale Lange could still spin a yarn. He could still recite the Lord’s Prayer. Still give his grandkids advice. Hold onto your stocks, you only lose money if you sell. Hold onto your family, they are everything you need.

He held on as long as he could. Those first months, with a broken body that had once carried his kids on his shoulders and buckled into roller coasters with his grandkids, he prayed to go to sleep and wake up in heaven.

But as the end approached, he didn’t seem as sure, holding our hands with his salesman’s grip and not letting go.

Jerrod and Laura are on the first lap of their married lives. My parents had 66 years behind them when Dad died May 28, 2022.

When they built the house with the dining room my mom wanted in 1990, they offered to sell me my childhood home, a ’60’s brick ranch with oak floors they’d promptly covered in shag carpet. I politely declined. I wanted a grownup life, done my way.

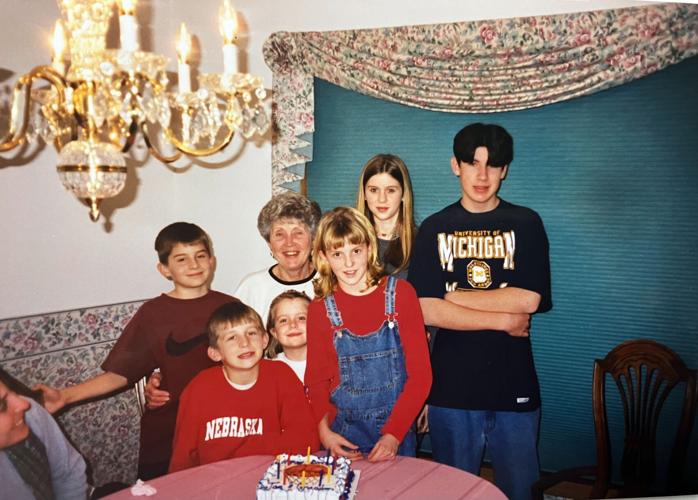

Arly Lange at the dining room table in the ’90s, surrounded by six of her grandchildren. The table found a new home with Jerrod Bley and Laura Yeramysheva-Bley, a Lincoln couple who are furnishing their first home entirely secondhand.

Now I poke around estate sales, looking for mid-century treasures for my own brick ranch.

I peruse the leftovers of long lives, laid out on card tables and kitchen counters. The good dishes, the paring knives, the placemats. Christmas decorations and board games for the grandchildren who once came to play. And usually, in the bathroom or leaning on the washer and dryer — walkers and lift belts, canes and commodes.

You can watch life unspool in those houses: party dresses and dapper Sunday suits in the dim backs of closets, Velcro shoes and denture cases under the sink. The decades compressed, like a time-lapse video.

***

When Laura met Jerrod in 2006, she was a combat medic on deployment in Alaska with the Nebraska Army National Guard. Her friends back home gave the Marine who caught her fancy a nickname: Mr. Nine Days.

“I was there for two weeks and I met him five days after we arrived,” says Laura, 37, juggling Embry on her hip.

A few years later, in love and out of the military, Jerrod enrolled at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, eventually earning two degrees.

During those early dating years, Laura shipped off to Iraq and Jerrod walked the Appalachian Trail.

The Ohio native had an epiphany on his five-month trek, meeting environmentalists and hippies and hikers who’d lost their jobs during the 2008 recession: Humans can limit environmental degradation by changing their consumption habits.

“It affected me so much, I came back and changed my major from civil engineering to environmental studies.”

Laura had a similar realization during her year in the Middle East, delivering food and water to schools, seeing the children delight at the watch on her wrist and the ballpoint pen she carried.

“They didn’t have much and at the same time they were very happy,” she says. “That put things into a global perspective for me.”

Laura’s family came to America as refugees and both she and Jerrod grew up surrounded by secondhand out of economic necessity, so it seemed natural to do the same.

And eventually, there were three more reasons: Leopold, Cora and Embry.

The parents wanted to do their part for the world their children would inherit.

“We are already facing a changing planet and a changing climate,” Jerrod says. “We recognize that over-consumption is connected to most of the climate change issues we have.”

They live intentionally. Cloth diapers. Food from local sources. A compost pile for their kitchen waste and grass clippings. Decade-old cars, one a hybrid.

Jerrod Bley uses reclaimed cedar fencing he found for free on Craigslist to build a picket fence around the vegetable garden in the backyard of his Lincoln home on July 22.

Jerrod found free lumber on Craigslist and is building a fence for their vegetable garden. He plans to remodel the kitchen and bathrooms with secondhand cupboards and vanities.

Everything in the house, save the couple’s mattress, is used: Lamps and side tables, couches and chairs, bedroom sets and patio furniture. The ’70s stereo console. The baby’s changing table. The art deco prints on the walls. The tchotchkes on the end tables. The wool rugs under their feet. Many of the clothes in their closets.

“Every time you extend the life of an object, it’s one less thing that needs to be built using resources from a finite planet,” Laura says.

Saving the gas and oil used to manufacture and transport. Saving trees. Saving space in landfills. Saving money, too.

“We’ve probably saved tens of thousands of dollars,” Jerrod says.

Their biggest ticket item? An antique oak bedroom set for $250.

My dad’s green armchair — free for the hauling — fits the budget and the living room’s boho vibe, with its strawgrass wallpaper, gold glass hanging light and a pair of gold glass lamps atop matching end tables.

On the day of my visit, Leopold and Cora are watching Russian cartoons on the same TV my parents once faithfully tuned to Husker football and ABC Nightly News in the family room.

I can see them there now, enjoying Lange Happy Hour with David Muir.

***

My dad wouldn’t have called himself an environmentalist.

But he’d holler at us to “Turn off the lights!” or to “Shut the door, you’re letting all the cold out,” when we’d stand too long in front of the refrigerator.

And he and my mom grew up in the days when everything was reused — The tin foil! Those rubber bands! The Cool Whip tubs! — and built to last.

He’d shake his head at broken toasters and plastic car bumpers. “They want it to break so you’ll buy a new one,” he’d say. “Junk!”

He wasn’t sentimental about stuff, but he’d be glad his furniture was making new memories with a new family. And like Jerrod and Laura, he had reasons for wanting the planet to endure.

Dale and Arly Lange with one of their 11 great grandchildren on Halloween 2019. Dale is sitting in the green armchair where he spent his mornings reading the paper and pondering his day.

I spent an afternoon last week scouring old albums for photos of my dad at the dining room table. It was the grownup table, reserved for holidays and birthdays, all the grandkids in the kitchen, until they became grownups, too, with kids of their own. Dad at one end, Mom at the other.

I couldn’t find the photo I was looking for and Mom said she wasn’t sure there was one.

But she could see him there, content with his lot in life, cocooned by the family he loved.

“Starting in on his second plate of food.”

The Flatwater Free Press is Nebraska’s first independent, nonprofit newsroom focused on investigations and feature stories that matter.

Download the new Lincoln Journal Star app.

Top Journal Star photos for August 2023

Kipton Fankhauser loses his shoe as he falls off of "War Dance" during Mutton Bustin' at the Lancaster County Super Fair on Tuesday, Aug. 8, 2023, in Lincoln.

Patrons enjoy the first weekend of the outdoor carnival during the Lancaster County Super Fair at the Lancaster Event Center on Saturday, Aug. 5, 2023, in Lincoln.

Syllas Daniels and Kaneka Taylor (right) hold on tight as they ride the Orbiter at the carnival during the Lancaster County Super Fair at Lancaster Event Center on Saturday, Aug. 5, 2023, in Lincoln.

A nun peruses the animals on display at Rabbit Row during the Lancaster County Super Fair at the Lancaster Event Center on Saturday, Aug. 5, 2023, in Lincoln.

Angelina Mojok waves to the camera as she rides the merry-go-round at the carnival during the at the Lancaster Event Center on Saturday, Aug. 5, 2023, in Lincoln.

Cally Sullivan, Hannah Munk, Noah Schmoll and his sister Jocelyn (from left) let their rabbits hop from the starting line as they compete in a rabbit race during the Lancaster County Super Fair at the Lancaster Event Center on Saturday, Aug. 5, 2023, in Lincoln.

Offensive lineman Yahia Marzouk and Brady Eickhoff (from left) spring out from under the chute while running a drill during a practice at Lincoln Northwest on Wednesday.

Nebraska middle blocker Andi Jackson blocks assistant coach Jaylen Reyes during practice Tuesday at Devaney Sports Center.

Lincoln Pius X's Hudson Schulz (left) tackles teammate Sebastian Morales during practice on Tuesday at Pius X High School.

A view of the Federal Legislative Summit on Tuesday at Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum in Ashland.

Nebraska's Bryce Benhart (left) and Brock Knutson practice on Tuesday, Aug. 8, 2023, at Hawks Championship Center.

Lincoln Southwest's Zak Stark makes a throw during a football practice on Monday, Aug. 7, 2023, at Lincoln Southwest.

An excavator tears bricks off Pershing Center on Monday as demolition work begins in earnest on the former civic auditorium. Bringing down the structure is expected to take two to three weeks.

Young dancers spin one another as they perform a traditional dance with Wilber Czech Dancers during the annual Wilber Czech Festival on Saturday. The celebration will continue Sunday with a parade, motorcycle show, eating contest and much more.

Teams shoot around in the common area as they prepare to compete against one another during the 3-on-3 Railyard Rims basketball tournament at The Railyard on Friday, Aug. 4, 2023, in Lincoln. In collaboration with the Downtown Lincoln Association, the YMCA of Lincoln hosted the seventh annual Railyard Rims August 4-5. This 3-on-3 tournament takes basketball to the streets of the Railyard.

Callum Anderson gets his first haircut from barber Dean Korensky as he sits with his mother, Courtney Anderson, on Thursday at 33 Street Hair Studio. Callum was the fifth generation of the Anderson family to get a haircut from Korensky.

Carter Worrell has a staring contest with a baby chick during the Lancaster County Super Fair at Lancaster Event Center on Aug. 3, 2023.

A Nowear BMX rider jumps from a high ramp while teammates watch during the Lancaster County Super Fair at Lancaster Event Center on Thursday.

Zack Mentzer peeks out from a trailer while he and his family unload their Hampshire cross breed pigs the day before the start of the Lancaster County Super Fair at the Lancaster Event Center on Aug. 2, 2023.

Fair kids who show animals will set up in the stalls so they have a place to rest, the day before the start of the Lancaster County Super Fair at the Lancaster Event Center on Aug. 2, 2023.

Jen Witherby (left) and Mary Weixelman, bought 3 Daughters, last month and just recently completed their first week as owners.

Cooper Jordan, 4, runs the spray of a soaker hose during Sprinkler Day at the Eiseley Branch Library on Monday.

Protester Kari Wagner holds up a sign as Nebraska State Board of Education member Kirk Penner walks by in the Capitol on Monday.

Mack Splichal, 2, shows off his cheer moves to Nebraska cheerleaders Sidney Doty, Carly Janssen and Audrey Eckert (from left) during Nebraska Football's annual fan day at Hawks Championship Center on Sunday, July 30, 2023.

Shoes lost by previous skydivers are hung above the exit to the runway at the Lincoln Sport Parachute Club on Saturday, July 29, 2023, in Weeping Water.

Carpet Land players watch from the dugout as their team bats in the first inning during the Class A American Legion championship on Saturday at Den Hartog Field.

Nebraska's Darian White (left) talks with teammate Callin Hake during a team practice Thursday at Hendricks Training Complex.

Ten-year-old Connor Horner plays in the sprinkler fountain at Centennial Mall across from the state Capitol on Monday, as temperatures reached the 90s and the heat index reached into triple digits. The Lincoln Parks and Recreation Department said it discourages people from playing in the Centennial Mall fountains because the water is not treated.