It wasn't supposed to happen so quickly.

After the atomic bomb test in New Mexico and the bombings of Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, and Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945, U.S. military intelligence had it that the Soviet Union might need until 1953 to bring a nuclear weapon to the production stage.

In the current film "Oppenheimer," an account of the life of American physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer and his direction of the Manhattan Project, which produced the bombs, the idea of the Soviets obtaining a nuclear weapon is almost treated as an afterthought by scientists and military men. With World War II raging, the greatest concern was Nazi Germany producing a bomb.

Even after the war ended, estimate about when the Soviet Union would obtain one were conservative. A CIA file from October 1946 shows as much. "It is probable that the capability of the U.S.S.R. to develop weapons based on atomic energy will be limited to the possible development of an atomic bomb to the stage of production at some time between 1950 and 1953. On this assumption, a quantity of such bombs could be produced and stockpiled by 1956."

People are also reading…

On Aug. 29, 1949, the Soviet Union tested its first nuclear bomb.

Less than a year before, on Oct. 6, 1948, George Abramovich Koval hopped on board an ocean liner in New York City bound for Le Havre, France. By all accounts, it's the last time he ever saw his homeland.

This photo of George Koval and an unknown woman appears in the Federal Bureau of Investigation's files on the Soviet spy. According to the FBI, the photo was probably taken sometime in the summer of 1947. Koval, who was born in Sioux City, acted as a Russian operative.

For the prior decade, Koval, born in Sioux City, Iowa, on Christmas Day 1913 and a 1929 graduate of Central High School, worked as an spy for the Soviet Union. In that time, he'd moved from a Soviet front company in New York City to a U.S. Army Specialized Training Program in Charleston, South Carolina, to a Special Engineer Detachment which got him a job in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, as the U.S. military was enriching uranium and working with plutonium there.

"He had access to material that could have varied from 'unclassified' to 'top secret,'" an FBI file on Koval says. And he sent as much of that information as he could to a Soviet agent named Clyde.

Koval was one of two Siouxland natives with ties to the development of the atomic bomb.

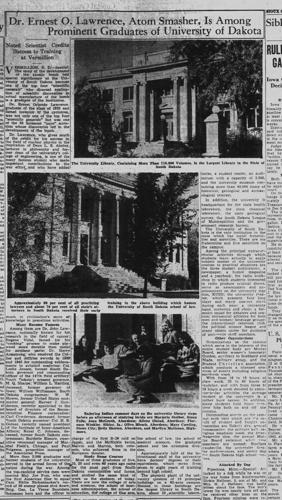

Nobel laureate was a South Dakota ticket taker and wafflemaker

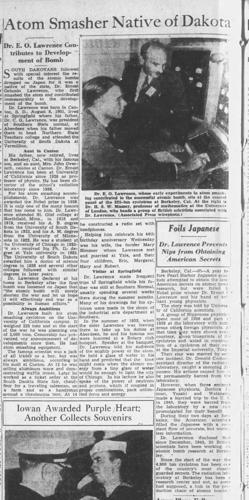

After the mushroom cloud appeared over Hiroshima, Ernest Orlando Lawrence, a University of South Dakota graduate and winner of the Nobel Prize in physics, reportedly said, "The atomic bomb will surely shorten the war and let us hope it will effectively end war as a possibility in human affairs."

In the film "Oppenheimer," and on the Manhattan Project itself, is one of the men working on uranium enrichment.

A native of Canton, South Dakota, Lawrence was born Aug. 8, 1901. He's also the man responsible for the creation of the cyclotron.

"What the cyclotron can do is get particles to really high energies; they can get them moving really fast, which means they have a lot of energy. And when you have particles with really high energies that you collide together, you start to see really interesting physics happen," said Tina Keller, a physics professor emeritus at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion.

Lawrence built his first cyclotron in 1930. It cost him $25 and was fashioned from a small vacuum pump and copper pieces. A number of sketches he did of the cyclotron were made in the shops of the industrial arts department at Southern State Normal in Springfield, South Dakota, while his father, Carl Gustavus Lawrence, was college president.

"Lawrence was this unique person who both liked the theory but also wanted to get his hands dirty," Keller said.

An article that appeared in The Journal on Aug. 12, 1945, summarized Lawrence's early life in South Dakota: At age 12, Lawrence sold aluminum ware and did demonstrations of waffle irons. At 14, Lawrence constructed a radio set with headphones. During his tenure at USD, he built the first campus radio station. He also spent part of his youth as a ticket seller at the South Dakota State Fair, a chauffeur for a traveling salesman and a handyman.

From left to right: Ernest O. Lawrence, Enrico Fermi, and Isidor I. Rabi. This photo was most likely taken at the Nuclear Physics Conference in Los Alamos, New Mexico, in August 1946. Lawrence was a graduate of the University of South Dakota.

When Lawrence got to Vermillion in 1920, the school didn't offer a physics degree. So he pursued a chemistry degree while taking one-on-one physics courses with professor Lewis Ellsworth Akeley.

"What Akeley did is, there was the new physics that was happening in Europe, quantum mechanics, and Akeley told Lawrence: 'There's going to be papers in the journals that are talking about this new physics, and you're gonna teach it to me.'"

Keller said such a role reversal would've greatly helped Lawrence because "to teach something, you need to understand it a lot better than sitting in the classroom and listening to it."

Lawrence finished at Vermillion in 1922 and pursued further degrees at the University of Minnesota, Yale and the University of California, Berkeley, where he perfected the cyclotron.

Soviet spy was an Iowa high school debater

George Koval's life growing up in Sioux City was a life of letters as well.

Koval and his brothers Isaya and Gabriel were second-generation immigrants. Their parents, Abram and Ethel Koval, fled anti-Semitic violence in what is now Belarus and eventually made a home for themselves at 619 Virginia St., in a building that no longer stands.

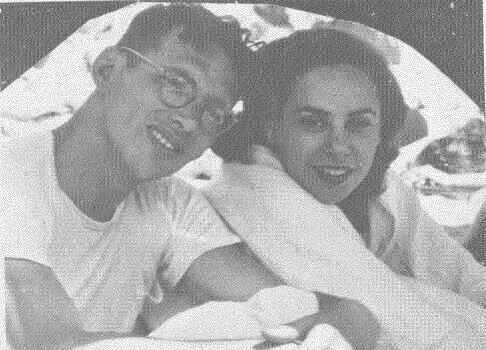

George Koval graduated from Central High School in Sioux City in 1929.

"They spoke Yiddish but their children were taught English and they wanted their kids to be avid readers," said Ann Hagedorn, a Wall Street Journal reporter who wrote a 2021 book about Koval, "Sleeper Agent: The Atomic Spy in America Who Got Away."

Hagedorn said Koval was such a lover of books that he became the president of the Chrestomathian Literary Society at Central High School. He graduated at age 15 in 1929, and was an interscholastic debater, honor society student and prominent in the annual class play.

"Ranked as one of the first three in scholarship, leadership and character," a June 2, 1929 Journal article said of the future Soviet spy.

A Feb. 15, 1929 Journal article notes his debate team won a competition in Vermillion. The debate question was whether the United States should "cease to protect by armed forces, American capital invested in Latin-American countries except after formal declarations of war." Koval, who served as a delegate for the Iowa faction of the Young Communist League, argued against U.S. military activity in Central America.

"We have to all realize he grew up in a household where the quest of his parents and their colleagues was to end world oppression," Hagedorn said.

'Radical released after father promises to make him behave'

In September 1931, about two years after he'd graduated from Central High, Koval led a crowd of about 40 people into the office of Charles Lebeck who helped administer relief aid. By then, the Great Depression was entering its severest phase; accompanying it was an increase in leftist activity.

Koval and several dozen people, described as a "mob" in Journal reporting, demanded assistance for two women in the crowd who, he said, were destitute.

"Koval was not satisfied when Lebeck said he’d investigate the cases and reportedly threatened (him) before leaving and then returning. He was arrested by Woodbury County deputy sheriffs and placed in a cell overnight," The Journal reported at the time.

When Sheriff John Davenport asked Koval if he would promise to stay away from the courthouse and cause no further disturbance, Koval is said to have refused to make such a promise. The story, headlined, "Radical released after father promises to make him behave," characterizes the still-young Koval as a man who "set out recently to reform the world."

George Koval, a 1929 Central High School graduate and later a spy who leaked secrets of the Soviet Union, was noted for his leftist political leanings. In September 1931 he was arrested in Sioux City for leading a mob against the "overseer of the poor."

Within a year of George Koval's arrest, the entire Koval family left Sioux City and returned to Russia to try collectivist farming near the Manchurian border. There is no record of any of them ever returning to the area.

Abram Koval, who worked as a carpenter in Sioux City, had served as a representative for the Organization for Jewish Colonization in Russia -- a communist-backed organization that supported Jews who wanted to live in new collective settlements in the Soviet Union.

"In the 1930s, since Stalin was such an immensely successful propagandist, they believed he had the key. Capitalism was having a wobbly period," Hagedorn said.

Smithsonian Magazine's May 2009 story about Koval, "George Koval: Atomic Spy Unmasked," said he improved his Russian as he worked on the farm in Birobidzhan. Him mastering the language helped get Koval into Moscow's Mendeleev Chemical Institute.

Koval met and married his wife, Lyudmila, over the course of his time at Mendeleev. He graduated five years later, with honors, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

The front of one of the sections of George Koval's FBI files is shown here. The intelligence agency's documents on Koval run in the thousands of pages and Sioux City is mentioned throughout.

A year of war and awards

For Koval and Lawrence, 1939 was a life-changing year.

On Nov. 9, 1939, Lawrence received the Nobel Prize in physics for his development of the cyclotron. A wire story in The Journal said he "gained the prize for invention and development of the cyclotron and the results obtained with it, especially in connection with artificially radioactive elements." When Lawrence's parents were asked for comment, his father was out hunting pheasants near the family's South Dakota home and his mother, Gunda, was "unable to comment for excitement."

Throughout spring and summer of 1939, Koval, then a recent Mendeleev graduate, gave serious thought to going back to school. He was living in a house owned by his wife's family. But, as was common in the Soviet Union, they didn't live alone. Hagedorn said a number of other families occupied the space, and at least one resident was documenting Koval family indiscretions, like a cousin defecting and no one reporting it.

Prof. Ernest O. Lawrence, a graduate of the University of South Dakota in Vermillion, later played a significant role in the Manhattan Project.

"Every time something started to go wrong or get shaky, George went back to school," Hagedorn said.

Two factors complicated Koval's dreams of returning to the classroom.

For one, he was being groomed by Soviet military intelligence. In Koval, they had a man who was intimately familiar with American culture, which would cut down on training time. He'd grown up in the heartland, was a baseball fan and could easily quote American authors.

A June 2017 piece from the BBC noted that Yuri Drozdov, a high-ranking official within Soviet Union's KGB intelligence agency, once said it could take as many as seven years to train a Soviet spy. But Koval?

"He was in training for about a year," Hagedorn said.

The reason Koval came to train with Soviet intelligence is the second complication of his graduate school plans. Nazi Germany invaded Poland on Sept. 1, 1939. Hagedorn said what might've previously been an option for Koval (taking up the profession of spy craft) became more of an ultimatum.

"He didn't have a choice," she said. "He was probably told over and over again, your family will be protected if you join the GRU."

A fake job with the Raven Electric Company

The Smithsonian Magazine story includes recollections about Koval from a man named Arnold Kramish who'd befriended Koval. One bit of correspondence explains how, when and where Koval returned to his first homeland.

"I entered the U.S. in October 1940 at San Francisco ... Came over on a small tanker and just walked out through the control point together with the captain, his wife and little daughter, who sailed together with him," the Smithsonian article quotes.

FBI records show that in January 1941, Koval registered for the military draft in New York City.

"On his questionnaire dated March 19, 1941, he indicated he attended the State University of Iowa for two-and-one-half years, during which time he studied electrical engineering." The cover job Koval landed was with Raven Electric Company, a front for Soviet intelligence.

Prof. Ernest O. Lawrence, a graduate of the University of South Dakota in Vermillion, later played a significant role in the Manhattan Project.

In the early 1941, Lawrence began considering an electromagnetic method to separate larger, purer uranium-235 isotopes. Keller said most natural uranium is uranium-238 which does not fission easily. The fission process is crucial for nuclear weapons as it releases massive amounts of energy.

"What you really need is the specific isotope of uranium that will undergo this chain reaction fission process such as uranium-235," she said.

The device that helped facilitate the work was called the "calutron" and it was used at the U.S. government's uranium enrichment plant in Oak Ridge, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

FBI files show Koval was fingerprinted as a mathematician on Aug. 15, 1944, and worked in the health physics department at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

"What that meant on a daily basis is he was required to measure levels of radiation contamination as a required work routine. That gave him information about every one of the facilities at Oak Ridge," Hagedorn said.

One of those facilities would've been the Y-12 Electromagnetic Plant which Lawrence did significant design, construction and operation work in beginning in 1943.

In less than a year's time, Koval was reassigned from Oak Ridge to a Manhattan Project laboratory in Dayton, Ohio. Scientists there were tasked with purifying polonium which was used as the initiator for the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

After the war, both men remembered for their atomic connections

Soviet intelligence demands for Koval's spy craft diminished after the end of World War II with the surrender of Japan. From February 1946 until October 1948, when he left America forever, Koval kept a low-profile, Hagedorn said.

"If you read the description of him from his landlady in the Bronx, she described him as this introverted, hardworking, very quiet guy," Hagedorn said. After he was discharged from the Soviet military, Koval became a teacher at the Mendeleev Institute.

Lawrence's time after the war was spent pushing for more public funding of large-scale scientific research, advocating for the development of the hydrogen bomb and trying to help negotiate a proposed "Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty" with the Soviet Union. Lawrence grew keener on the hydrogen bomb as a possible U.S. military weapon after the Soviet Union's successful test in August 1949.

The negotiating effort was requested by then President Dwight D. Eisenhower. While in Geneva, Switzerland, to negotiate and listen to talks about the scientific detection of nuclear explosions, Lawrence became ill. A month later, on Aug. 27, 1958, he died at the age of 57. A Journal editorial after his passing referred to him as a "son of Siouxland."

Prof. Ernest O. Lawrence, a graduate of the University of South Dakota in Vermillion, later played a significant role in the Manhattan Project.

"Few scientists played a more prominent role than Dr. Lawrence did in the advancing atomic age, from the dawning, through the diversion to war purposes to the atoms-for-peace era and the earnest search for means to limit nuclear explosions," the editorial read.

Now, the science center at the University of South Dakota is named for Lawrence and Akeley. There's also a scale model of a cyclotron and a large portrait of Lawrence visitors to the Vermillion campus can see.

"I’ve always been proud of the fact that Lawrence was a USD grad and won the Nobel Prize in my discipline," Keller said.

When Koval died in Moscow on Jan. 31, 2006 at age 92, praise of him in American and Russian media was scant. But the next year, in November 2007, the office of Russian President Vladimir Putin released a statement hailing Koval as "the only Soviet agent who infiltrated secret U.S. nuclear facilities which produced plutonium, enriched uranium and polonium for building atomic weapons." For his work, Koval, who went by the code name "Delmar," posthumously received the title of "Hero of the Russian Federation."

In June 1946, Ernest Lawrence's father gave a speech to the Sioux Falls Cosmopolitan Club. The subject was the atomic bomb.

"Ways must be found to control the destructive use of the atomic bomb, 500 of which could destroy all American cities of 50,000 population and over," Carl Gustavus Lawrence said. "We’ve got the secret but we can’t keep it. Other nations have able scientists working on the same thing."

At least part of the information Soviet scientists were working off of came from Sioux City's George Koval.

This photo shows the Trinity Test mushroom cloud. On July 16, 1945 Los Alamos scientists successfully conducted the world’s first nuclear weapons test.

Photos: See historic photos of the Hiroshima atomic bombing 75 years ago

FILE - In this Aug. 6, 1945, file photo released by US Air Force, a column of smoke rises 20,000 feet over Hiroshima, western Japan, after the first atomic 5-ton "Little Boy" bomb was released. Hiroshima was targeted because it was a major Japanese military hub filled with military bases and ammunition facilities. The city of Hiroshima on Thursday, Aug. 6, 2020 marks the 75th anniversary of the world’s first nuclear attack. (George R. Caron/US Air Force via AP, File)

FILE - In this Aug. 6, 1945, file photo, smoke rises 20,000 feet above Hiroshima, western Japan, after the first atomic bomb was dropped during warfare. Hiroshima was targeted because it was a major Japanese military hub filled with military bases and ammunition facilities. The city of Hiroshima on Thursday, Aug. 6, 2020 marks the 75th anniversary of the world’s first nuclear attack. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - This Aug. 6, 1945, file photo released by the U.S. Air Force shows the total destruction of Hiroshima, western Japan, as the result of the first atomic bomb dropped. An estimated 140,000 people, including those with radiation-related injuries and illnesses, died through Dec. 31, 1945. That was 40% of Hiroshima’s population of 350,000 before the attack. (U.S. Air Force via AP, File)

FILE - In this Aug. 6, 1945, file photo released by the U.S. Air Force, white smoke rises from detonation of the atomic bomb over Hiroshima, western Japan. At 8:15 a.m., the U.S. B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped the 4-ton “Little Boy” uranium bomb from a height of 9,600 meters (31,500 feet) on the city center, targeting the Aioi Bridge. The bomb exploded 43 seconds later, 600 meters (2,000 feet) above the ground. (U.S. Air Force via AP, File)

FILE - In this Sept. 5, 1945, file aerial photo, the landscape of Hiroshima, western Japan, shows widespread rubble and debris, one month after the atomic bomb was dropped. An estimated 140,000 people, including those with radiation-related injuries and illnesses, died through Dec. 31, 1945. That was 40% of Hiroshima’s population of 350,000 before the attack. (AP Photo/Max Desfor, File)

FILE - In this Aug. 6, 1945, file photo, survivors are seen as they receive emergency treatment by military medics shortly after the first atomic bomb ever used in warfare was dropped by the United States over Hiroshima, western Japan. Many people exposed to radiation developed symptoms such as vomiting and hair loss. Most of those with severe radiation symptoms died within three to six weeks. Others who lived beyond that developed health problems related to burns and radiation-induced cancers and other illnesses. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Sept. 8, 1945, file photo, an allied correspondent stands in a sea of rubble before the shell of a building that once was a movie theater in Hiroshima, western Japan, a month after the first atomic bomb ever used in warfare was dropped by the U.S. to hasten Japan's surrender. Many people exposed to radiation developed symptoms such as vomiting and hair loss. Most of those with severe radiation symptoms died within three to six weeks. Others who lived beyond that developed health problems related to burns and radiation-induced cancers and other illnesses. (AP Photo/Stanley Troutman, Pool, File)

FILE - In this Aug 8, 1945, photo, soldiers and civilians walk through the grim remains of Hiroshima, western Japan, two days after the atomic bomb explosion. The building on left with columned facade was the Hiroshima Bank. To its right, with arched front entrance, was the Sumitomo Bank. An estimated 140,000 people, including those with radiation-related injuries and illnesses, died through Dec. 31, 1945. That was 40% of Hiroshima’s population of 350,000 before the attack. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - In this Sept. 7, 1945, file photo, an unidentified man stands next to a tiled fireplace where a house once stood in Hiroshima, western Japan. The Aug. 6, 1945, bombing was the world’s first nuclear attack. An estimated 140,000 people, including those with radiation-related injuries and illnesses, died through Dec. 31, 1945. That was 40% of Hiroshima’s population of 350,000 before the attack. (AP Photo/Stanley Troutman, Pool, File)

FILE - In this Sept. 8, 1945, file photo released by U.S. Air Force, two people walk on a cleared path through the destruction resulting from the Aug. 6 detonation of the first atomic bomb in Hiroshima, Japan. An estimated 140,000 people, including those with radiation-related injuries and illnesses, died through Dec. 31, 1945. That was 40% of Hiroshima’s population of 350,000 before the attack. (U.S. Air Force via AP, File)

FILE - In this Aug. 6, 1945, file photo, the "Enola Gay" Boeing B-29 Superfortress lands at Tinian, Northern Mariana Islands, after the U.S. atomic bombing mission against the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Enola Gay dropped the 4-ton “Little Boy” uranium bomb from a height of 9,600 meters (31,500 feet) on the city center, targeting the Aioi Bridge. (AP Photo/Max Desfor, File)

FILE - In this Aug. 7, 1945, file photo, Col. Paul W. Tibbets, standing, pilot of the B-29 Enola Gay which dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, western Japan, describes the flight during a news conference at Strategic Air Force headquarters on Guam, one day after the atomic bombing. At 8:15 a.m., the U.S. B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped the 4-ton “Little Boy” uranium bomb from a height of 9,600 meters (31,500 feet) on the city center, targeting the Aioi Bridge. (AP Photo/Max Desfor, File)

The Atomic Bomb Dome is seen at dusk in Hiroshima, western Japan, Sunday, Aug. 2, 2020. The city of Hiroshima on Thursday, Aug. 6 marks the 75th anniversary of the world’s first nuclear attack. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

The Atomic Bomb Dome is seen at dusk in Hiroshima, western Japan, Monday, Aug. 3, 2020. The city of Hiroshima on Thursday, Aug. 6 marks the 75th anniversary of the world’s first nuclear attack. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

The Atomic Bomb Dome is seen at dusk in Hiroshima, western Japan, Sunday, Aug. 2, 2020. The city of Hiroshima on Thursday, Aug. 6 marks the 75th anniversary of the world’s first nuclear attack. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

A man looks at the Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima, western Japan, Sunday, Aug. 2, 2020. The city of Hiroshima on Thursday, Aug. 6 marks the 75th anniversary of the world’s first nuclear attack. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Hatsue Onda, center, is helped by Kengo Onda to offer strings of colorful paper cranes to the victims of the 1945 Atomic bombing near Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in Hiroshima, western Japan, Monday, Aug. 3, 2020. The origami cranes that can be seen throughout the city became a symbol of peace because of atomic bomb survivor Sadako Sasaki, who, while battling leukemia, folded similar cranes using medicine wrappers after hearing an old Japanese story that those who fold a thousand cranes are granted one wish. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

People pray in front of the cenotaph for the atomic bombing victims before the start of a ceremony to mark the 75th anniversary of the U.S. bombing in Hiroshima, western Japan, early Thursday, Aug. 6, 2020. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

People pray in front of the cenotaph for the atomic bombing victims before the start of a ceremony to mark the 75th anniversary of the U.S. bombing in Hiroshima, western Japan, early Thursday, Aug. 6, 2020. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Kazumi Matsui, right, mayor of Hiroshima, and the family of the deceased bow before they place the victims list of the Atomic Bomb at Hiroshima Memorial Cenotaph during the ceremony to mark the 75th anniversary of the bombing at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park Thursday, Aug. 6, 2020, in Hiroshima, western Japan. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Visitors observe a minute of silence for the victims of the atomic bombing, at 8:15am, the time atomic bomb exploded over the city, at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park during the ceremony to mark the 75th anniversary of the bombing Thursday, Aug. 6, 2020, in Hiroshima, western Japan. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Visitors observe a minute of silence for the victims of the atomic bombing, at 8:15am, the time atomic bomb exploded over the city, at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park during the ceremony to mark the 75th anniversary of the bombing Thursday, Aug. 6, 2020, in Hiroshima, western Japan. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)